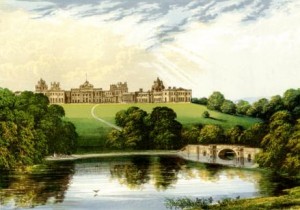

Engraving of Blenheim Palace

In the long twilight of the Victorian age, the British aristocracy quailed at the thought a new era might be about to dawn. One in which they could no longer count on the exclusive access to power they had once enjoyed, or on the income to maintain their enormous houses. They were saved by an influx of new blood – and, at least as importantly, new money.

In the forty years between 1880 and 1920, it has been estimated that more than three hundred scions of the Old World European nobility married wealthy New World brides. Between 1890 and 1910 alone, as many as a quarter of the marriages made by Britain’s young noblemen were to American heiresses.

There was a special magazine called The Titled American, giving details of marital possibilities – a kind of print marriage agency. One US newspaper piece published a picture of all available dukes asking: ‘American heiresses – what do you bid?’ A Puck cartoon of the ‘American Gold Fields’ showed a boatload of coroneted men, with a marriage license wrapped around their spade, each digging up a girl who comes out of the ground clutching a bulging bag of dollars.

So what did the so-called Dollar Princesses actually do for Britain? (Besides giving us Downton Abbey’s countess Cora – played by Elizabeth McGovern, who presents the series, Million Dollar American Princesses, starting tonight on ITV3.) Well, for a start, many of our stately homes would not be here without it. Blenheim Palace, seat of the Spencer-Churchill family, benefited from a series of American brides, and from their money.

The widowed Lilian Hammersley was no beauty when she met the divorced 8th Duke of Marlborough. (His brother Randolph Churchill would write that her moustache and beard ‘are becoming serious’.) But she had ‘lots of tin’. The tin paid for the roof of Blenheim Palace to be releaded, and gas and electricity installed, before the 8th Duke died – paving the way for his son, the 9th duke, in 1895 to marry Consuelo Vanderbilt, perhaps the most famous Dollar Princess of all.

Traces of Consuelo can be found all over Blenheim, from the portraits on the walls to the fabulous Renaissance cradle given by her mother Alva. When his marriage to Consuelo marriage broke up, the Duke would marry yet another American, who became the model for the sphinxes which decorate the garden today. And Blenheim was also familiar territory to the first of the great American heiresses – Jennie Jerome, bride to Lord Randolph Churchill, whose son Winston would be born there.

Jennie Churchill epitomised the ‘snap’ and force of the first American Beauties – better dressed and better educated than their homegrown rivals, arriving from the New World at a time when Britain was already on the cusp of change, with calls for the emancipation of women and a freer passage between the different classes of society. Jennie wrote that any American bride was assumed to be something between ‘a Red Indian and a Gaiety Girl’, her money the only thing she could possibly have to offer – but the heiresses would prove to be bringing new ideas as well as new money.

The idea that a woman need not submerge her own identity in that of her family; that everyone has the right to invent themselves, to forge their own future . . . The ideas, in short, that would lead us into the twentieth century.

‘The best class of women from the New World have done much to change the face of London society’, wrote Tatler magazine in 1910. ‘ In a word, they have brought the grit and ‘go’ of a new race to bear on our rusty if cherished institutions. They have made us more modern in our ways and more up-to-date in our opinions; they have taught us how to manage the mere man, and how to rule our own houses and keep our own money. In a word, they opened our eyes to women’s rights long before we ever heard of a Suffragette demonstration.’

Perhaps after all it is no coincidence that the first woman to take her seat as an MP in the British Houses of Parliament was an American, Nancy Astor, ironic though the fact may seem to be.

But there is one other thing we owe to the Dollar Princesses – the present and future shape of the royal family. We’re not talking about Edward VII’s noted fondness for the pretty, lively, US ladies, nor yet about Wallis Simpson and Edward VIII. No – few know that Diana, Princess of Wales, was descended from Dollar Princess stock. Or could we have guessed it, maybe?

It all comes down from one Frances, ‘Fanny’, Work; who in 1880 made a runaway the future Baron Fermoy, James Roche, to the horror of her New York stockbroker father. Fanny divorced her profligate husband under American law in 1891 (though Roche tried to sue Burke’s Peerage for listing the fact) – and in Fanny’s next disastrous match with a Hungarian riding instructor, it’s hard not to see echoes of her granddaughter, Frances Shand Kydd, and of her daughter Diana.

But the story is stranger than that, actually. Fanny’s self-made father Franklin was so fanatical an American patriot that he tried to disinherit any of his descendants who married a foreigner – and to disinherit Fanny’s sons if ever they set foot on English soil. Prince William, of course, is his great-great-great-grandson . . . Whatever would the old man have said? Would he have seen it as an outrage – or as the final victory of the American Beauty?